Given the disturbing interest that some in the Reformed world are showing for Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) and National Socialism, and the accompanying rise in antisemitism, I have been doing some reading on early Christian responses to Nazism in the 1920s and 1930s. I am interested to see what concerns Christian leaders had in the early days of Hitler’s rise to power so as to be aware of those same issues in our own. Readers of The Last Resort will note that I have spent time reading Dietrich von Hildebrand (1889-1977), one of the earliest critics of Hitler. His book My Battle Against Hitler is very helpful. It shows not only Hildebrand’s precience, but also his strength of character, as he was willing to lose all for the sake of truth and justice. Now that I am finished his memoir, I am reading Alice von Hildebrand’s (1923-2022) biography of her husband, which is likewise quite helpful, even if its hagiography can get a little much at times. Regardless, it fills in gaps that are missing in the memoir, particularly Hildebrand’s early life and upbringing.

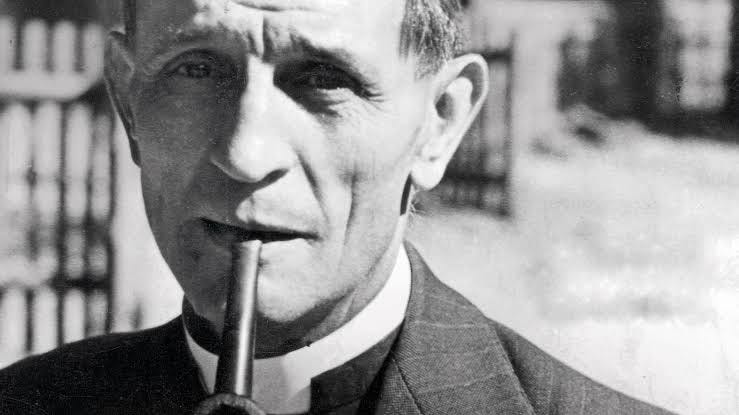

I am also looking more casually at a key Protestant critic of Hitler, namely the German pastor Martin Niemöller (1892-1984), who famously stood Hitler down face-to-face. This act, and his other acts of resistance, got him imprisoned. He was first jailed at Moabit Prison (1937), and upon his release after his trial (where he was supposed to have been granted his freedom), he was captured by the gestapo and put in the concentration camps at Sachsenhausen (1938) and Dachau (1941). Unlike his Protestant colleague, Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945), Niemöller (pictured above) was released after the war and was able to live a long life in service of the global church. Like Bonhoeffer, however, he also wrote a series of letters from prison. Bonhoeffer’s letters, penned from Tegel Prison before his execution, have become something of a Christian classic. Niemöller’s published letters, Exile in the Fatherland, that I am currently thumbing through, are from his first imprisonment at Moabit. Though they aren’t considered a classic like Bonhoeffer’s, they nevertheless are important for our understanding of the Christian resistance to Hitler.

I’m only just dipping into Niemöller’s letters and I probably won’t read him as thoroughly as I did Hildebrand’s memoir. However, I did want to share an observation drawn from the Introduction, written by the editor of the English edition of the letters, Hubert G. Locke, that I thought was relevant to our day. In the Introduction, Locke provides some background to help readers situate the various letters. As he was discussing the conditions leading up to the war, Locke naturally described the concerns of the German Christians living under the Weimar Republic in the 1920s. They were also fearful of the Communist threat posed by the Bolsheviks. Both of these contextual issues have parallels today and help account for the turn that some in the Reformed world are making towards totalitarianism, in the name of Protestant political theology.

One of the threats that Christians today are deeply concerned about is dubbed ‘Cultural Marxism.’ The term, interestingly enough, bridges the concerns that the Germans had over Communism, that was Marxist, and the sexual licentiousness that marked Weimar culture. Cultural Marxism is a version of the earlier, economic Marxism, that lay behind the Bolshevik ideology. Cultural Marxism, however, is less about the proletariat overthrowing the bourgeoisie and more about overthrowing the power structures in culture that oppress us, like the traditional values that Christians hold to. I am not commenting on the merits of the term, but what is interesting to note is that a significant part of the justification that Germans made in their minds as they supported Hitler was the threat of Communism and sexual license. In particular, they feared what the Nazis termed ‘Cultural Bolshevism’ (Kulturbolschewismus), that they saw was part of the degeneration of German culture under the Weimar Republic. The Nazis argued that Cultural Bolshevism, that expressed itself in art and music, and was often expressed through sexual license, was a threat to institutions like the family in Germany. In Mein Kampf, Hitler expressly criticised these issues, refering to ‘art Bolshevism,’ which he said was the ‘only possible cultural form and spiritual expression of Bolshevism as a whole.’ Locke quotes T. L. Jarman’s The Rise and Fall of Nazi Germany, that described Weimar Germany as ‘a country of modernism and freedom [and a] freedom degenerated into licence…Bars for homosexuals, cafes where men danced with men, new liberty between the sexes, nudism, camping, sun-bathing, pornographic literature in the corner kiosks.’ As Locke noted, ‘Because Hitler and National Socialism promised an end to these evils, they found widespread support among the Protestant and Catholic masses. Even the church hierarchy, which denounced Nazism on other grounds, was quite willing to accept and applaud its determination to stop the communist menace and to restore a climate of moral rectitude in the nation.’

This is not unlike what we are seeing today on a grander scale with the fears that Christians, as well as others, have with the LGBT+ movement as it reshapes traditional and Christian values in the West. It is worth understanding the fears of the Germans in the 1920s and be aware of reasons behind their willingness to accept totalitarianism, based as it was on the promise to overthrow the Weimar cultural order and re-establish older German cultural values. While Christians today are fearful of their rapidly changing culture, we must not fall to the grievous error that the German Christians fell into, of supporting a dictator who promises to save us from cultural decay. We most especially should not be thinking that Hitlerism in any way provides a safety-net for the church. Because as we saw in Germany (and many parts of Europe), the church was not protected, and was eventually persecuted, under Hitler. Let us instead share the mindset of Christians like Niemöller , Bonhoeffer, Hildebrand, Karl Barth, and many others, in resisting tyranny, even if that tyranny purports to share and protect our values. We should not be motivated by fear but by virtue.

I’ll close with a familiar quote attributed to Niemöller that is on display at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, that we would all do well to keep in mind:

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.